커피 브레이크 시간에 신간들을 둘러보다가 제목 때문에 클릭하지 않을 수 없었던 책은 제드 러벤펠드의 <살인의 해석>(비채, 2007). 분류상 '외국문학'이고 '미국문학'이고 '추리문학/미스터리'이다. 이런 부류의 책에 별로 흥미를 갖고 있지 않은데 (물만두님보다 먼저!) 소개를 거들게 된 건 순전히 제목에 대한 흥미 때문이다. <살인의 해석>? 프로이트의 <꿈의 해석>에 대한 비틀기 아닌가.

책에 대한 정보들을 읽어보니, 일단 저자가 흥미롭다. "프린스턴 대학 재학 당시 졸업논문으로 프로이트를 택했고, 줄리아드 연극원에 진학해 셰익스피어를 전공했다. 2007년 현재 예일대학 법과 대학원 교수로 재직 중이다. 지은 책으로 <살인의 해석>, <사법부에 의한 혁명 - 미국 헌법의 구조>, <시간 속의 자유 - 입헌 자치 정부 이론> 등이 있다"고 소개돼 있는데, 간단히 말해서 멀쩡한 법학자인데다가 명문 법대 교수가 아닌가(그의 아내마저 직장 동료라고 한다. 남편 이상으로 유명한 에이미 추아이다 ). 웬 스릴러? 아무래도 '문학적 끼'를 주체하지 못했나 보다. 미 헌법 전문가로 돼 있는데, 아무래도 전공은 형법쪽이어야 했을 거 같고.

). 웬 스릴러? 아무래도 '문학적 끼'를 주체하지 못했나 보다. 미 헌법 전문가로 돼 있는데, 아무래도 전공은 형법쪽이어야 했을 거 같고.

더 찾아보니 <살인의 해석>은 그의 첫 소설이다. 원저는 작년 9월에 나왔으니까 불과 6개월도 되지 않아 한국판이 나온 셈(이 순발력이라니!). 거의 '동시출간'이라고 봐야겠다. 일본소설들의 경우도 그렇거니와 이런 장르소설들에 오면 '문학의 위기'라는 게 적어도 상업적으로는 엄살에 지나지 않아 보인다. 그러니까 그 위기는 그냥 '특정한 한국문학의 위기'로 이해해야 하지 않나 싶고(물론 고진이 말하는 진지한 '근대문학'이라고 할 때는 사정이 또 다르지만).

소개에 따르면, "미국의 법률학자 제드 러벤펠드가, 20세기 사상가 프로이트와 융의 학설을 바탕으로 쓴 범죄 추리극. 실제로 있었던 역사적 사건들을 꼼꼼히 취재해 프로이트와 융을 살인사건에 개입시켰다. 20세기 초반 뉴욕의 풍경이 소설 속에서 생생히 묘사되며, 프로이트와 융의 정신분석학이 이야기 속에 아로새겨진다. 이야기는 프로이트가 실제로 미국을 방문한 해인 1909년 뉴욕을 배경으로 시작된다. 당시 뉴욕은 건축 산업의 발전으로 인해 인간의 어두운 욕망을 닮은 마천루들이 매일 경쟁하듯 세워지고 있었다. 그 고층 빌딩에서 어느 날 미모의 여성이 살해되고, 프로이트가 그 사건에 개입하게 된다."

그러니까 프로이트의 이론을 살인 해석에 갖다 쓰는 게 이나라 프로이트가 직접 등장하는 소설인 것. 현지에서 나온 한 서평을 보니 '프로이트가 햄릿을 만났을 때'란 제목을 달고 있다. 서평이라기보다는 작가 탐방 같은 기사이군. 책은 아직 나오지 않았으니까 기사부터 쉬엄쉬엄 읽어두면 되겠다.

Sat 29 Jul 2006

Sat 29 Jul 2006

When Freud met Hamlet

JACKIE McGLONE

JED RUBENFELD WEAVES HIS SILVER BMW SPORTS car expertly around the wide streets of New Haven, Connecticut, sighing heavily and murmuring that he wishes he could leave the country over the next few weeks. Certainly, he could afford to escape. The law professor at Yale University has recently received a whopping seven-figure sum for the sale of his first novel. He refuses to confirm the exact figure, but it is thought to be a US record.

Running away is not an option, however, since Rubenfeld becomes deputy dean of the law faculty at Yale in the autumn and his book, The Interpretation of Murder, is due out here next month and in September in the US. Already something of an international publishing phenomenon, the novel has been sold in 28 countries and his publishers have flown in fleets of booksellers to meet the "spectacularly entertaining storyteller". Soon, he faces a long, gruelling book tour across the States.

For once, though, the hype is not exaggerated. Rubenfeld's The Interpretation of Murder is a classy, literary crime novel that's also a thrilling, heart-in-the-mouth read. Set in early 20th-century Manhattan, it takes its inspiration from Sigmund Freud's visit to New York in 1909, accompanied by his protégé and rival Carl Jung. Once you start reading the atmospheric 400-page book, it's impossible to put down. Someone should snap up the film rights.

Bestseller-dom beckons, I tell 47-year-old Rubenfeld. He looks doubtful and insists that he awaits publication with trepidation. "I just don't want to be in this country when the reviews come out," he says over lunch.

His last book - Revolution by Judiciary: The Structure of American Constitutional Law - sold all of six copies when it came out last year. "And four of those were bought by members of my family!" Nonetheless, he has been described as "the most elegant legal writer of his generation," and his first academic tome, 2001's Freedom in Time: A Theory of Constitutional Self-Government, was acclaimed.

But, he says, a work of fiction is something else entirely, although "a very great deal" of The Interpretation of Murder is fact-based. "It's not a genre of literature with which I was familiar," says Rubenfeld, although he's since read Caleb Carr's The Alienist and Matthew Pearl's The Dante Club, and admires both. He wrote his first draft in six months. "It's doubly odd to me because I've never written a line of fiction before - The Interpretation of Murder just poured out.

"I was re-reading EL Doctorow's Ragtime while writing my own novel, mainly for his marvellous descriptions of turn-of-the-century New York, and I'd forgotten that Freud's visit to New York is mentioned in that book. He's a tremendous writer - if only I'd an eighth of his talent - but the details about Freud are not all that accurate because Doctorow is doing something much more fanciful than I am."

Rubenfeld spent months researching his novel. "You can get old newspapers on the internet now - a tremendous resource," he says. "I put countless hours into researching the New York City of 1909, which was far more fascinating than the city of my imagination. Sadly, I lack a vivid imagination. Taking so much from real life made the whole book possible."

As for the novel becoming a bestseller, he jokes: "I have to have a bestseller for my own self-respect." His wife is Amy Chua, also a professor of law at Yale. Her book, World On Fire - based on her immensely readable academic essays - argues that when Third World countries embrace democracy and free markets too quickly, ethnic hatred and even genocide can result. It has become an international blockbuster, reaching the dizzy heights of the New York Times bestseller lists this spring.

His wife is brilliant, he tells me over black bean soup. Indeed, The Interpretation of Murder was her idea and she's his most acute critic, along with their daughters, Sophia (13) and Louisa (10), who saw mistakes in the novel no-one else had spotted, starting on the very first page. For instance, Louisa noted that the sentence "Even the keening gulls could be only seen, not heard" should read "Even the keening gulls could be only heard, not seen".

"It took a ten-year-old to point this out, after the manuscript had been read by five or six editors, proofread by a dozen others, and countless agents!" he exclaims. "Our daughters are little geniuses; I don't know what we're going to do with them."

For Sophia and Louisa, he wrote a bowdlerised version of The Interpretation of Murder, lest anyone accuse him of corrupting minors since the book takes in not only the moneyed salons of Gramercy Park and glamorous society balls, but opium dens in New York's Chinatown, sleazy brothels and mental asylums. It also includes Rubenfeld's unique take on Freudian theory and the eternal mysteries of Hamlet, as well as discussions and descriptions of certain sadistic sexual practices.

The novel opens with Freud's arrival in New York to deliver a series of lectures at Clark University, in Worcester, Massachusetts. Shortly afterwards, the bound, whipped and strangled body of a wealthy young debutante is discovered in a luxurious Manhattan apartment. When another wealthy society beauty narrowly escapes a similar fate, the mayor of New York - George B McClellan, one of many historical figures featured in the gripping story - asks Freud to use his revolutionary new ideas about psychoanalysis to help the survivor recover her memory of the attack.

The 17-year-old girl is called Nora. "For Nora, read Dora, the young woman described in Freud's most controversial case history, which reads like a 19th-century sensation novel, and which I've always thought someone should fictionalise," says Rubenfeld, adding that Dora, whose real name was Ida Bauer, was not an American, although she died in New York in 1945.

Nora is by no means a carbon copy of Dora, but her predicament is the same: advances are made on her by her father's lugubrious best friend and her father refuses to take her side when she protests, because he's having an affair with his friend's seductive wife, to whom Nora is erotically attracted.

The Oedipal interpretation of Nora's hysterics, which Freud offers Dr Stratham Younger - the book's dashing main narrator who falls in love with Nora - is the actual interpretation that Freud offered the real-life Dora. The case fascinates Rubenfeld, as does Freud's brief American sojourn.

Despite the great success of the Viennese psychiatrist's visit to the US, he always spoke, in later years, as if some trauma has befallen him there. "Freud called Americans 'savages'. He blamed America for physical ailments that afflicted him long before 1909. His biographers have puzzled over this mystery, speculating about whether some unknown event might have happened in America that would make sense of his otherwise inexplicable reaction," says Rubenfeld.

While there is no evidence that Freud was ever asked to investigate a murder, Rubenfeld has drawn directly and extensively from letters, writings or other published sources for much of the dialogue attributed to both Freud and Jung in his novel.

Since Rubenfeld grew up in a highly intellectual household in Washington DC, he was steeped in the works of Freud from an early age. The son of a psychologist and psychotherapist father - "not a Freudian" - and a renowned art critic and biographer mother, he read philosophy and psychology at Princeton, before attempting to fulfil his lifelong ambition to act.

After graduating, he studied acting at the Juilliard School of Drama in New York, where he was one of 18 students chosen from 1,000 applicants. He spent a year "pretending to be an unemployed actor but being a well-employed waiter," suffering rejection after rejection at "cattle-call auditions".

Eventually, after failing to land a single role, he repaired to Harvard University, where he read law and met his wife. "I don't know how I became a professor. I swore I wouldn't become an academic. I wanted to be in the real world and to deal with people's real problems, but now I really love my job. "As for a sequel to the novel, well, the jury's out. I do have this day job and it's time I produced another legal work, which will probably sell another six copies." Before we part, I tell Rubenfeld how riveting I found his theories on Hamlet, although I won't ruin it for prospective readers by revealing his thoughts on the gloomy Dane. "I have to admit I am worried about that, too," he says. "I hope that I haven't written too highbrow a book. There comes a point in this novel when the demands on the reader are perhaps just too great."

To paraphrase his favourite Shakespeare play, the gentleman doth protest too much.

07. 02. 01.

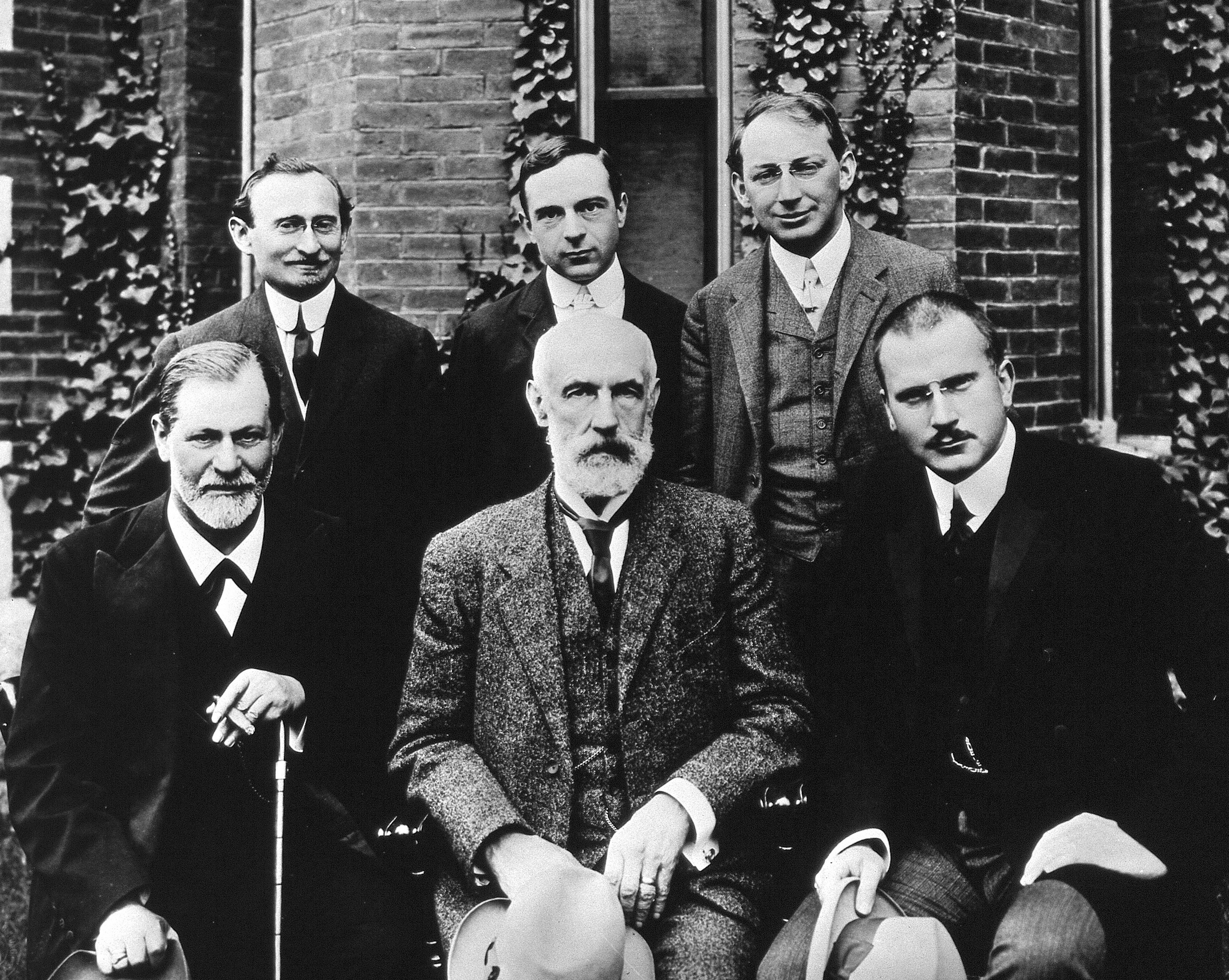

P.S. 사진은 소설의 배경이기도 한 1909년 클라크대학 앞에서 찍은 프로이트(앞줄 왼쪽)와 그의 수제자 융(앞줄 오른쪽)의 모습.